How Finalyse can help

NAVIGATE ESG DATA MANAGEMENT AND REPORTING SEAMLESSLY WITH OUR EXPERT GUIDANCE.

Integrating climate change risk into your ORSA, governance and risk-management system

Designed to meet Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) requirements

Evelyn is an actuary and Managing Consultant in Finalyse Dublin. She has 15 years’ experience between consulting and life industry. Evelyn has expertise in regulatory and financial reporting (Solvency II, BMA EBS, IFRS, US GAAP), actuarial and capital modelling, external audit, and risk management. She is currently focusing on climate change risk management and CSRD requirements.

As quarter four begins, most (re)insurers will have completed their ORSA process for the 2024 cycle. This has been the second annual ORSA cycle since EIOPA began to monitor the application of its Opinion on the supervision of the use of climate change risk scenarios in ORSA[1] (“EIOPA’s ORSA Opinion”) in April 2023. Finalyse has been on the journey with some of our clients, assisting them with integrating climate change risk into their risk management framework and documenting the process and conclusions for their ORSA. In this article, we reflect on what we have experienced and how things have settled, two ORSA cycles on.

The future state of the climate and knock-on climate-related impacts on the economy is an area of extreme uncertainty. Fulfilling the ORSA requirements has not been an easy task for any insurer, particularly when it comes to assessing climate change scenarios. EIOPA released their application guidance paper in August 2022[2] which included some practical examples of how this could be done. There is consensus that climate change can increase insurance underwriting risk, negatively impact asset values, and challenge business strategies. The industry is already seeing an uplift in claims linked to extreme weather events and this is generally expected to increase. For many insurers, however, the C-suite is still debating to what extent this is material for their business.

Climate change scenarios for insurers

Many insurers made use of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) climate and economic projections when creating climate change stress scenarios for their ORSA. These were referenced in EIOPA’s application guidance. In many cases, the results of the calculations became a barrier to drawing attention to the threat of climate change risk from the Board of Management and C-suite. The financial impacts of these scenarios on the investment portfolios of EU-based insurers have turned out to be relatively mild.

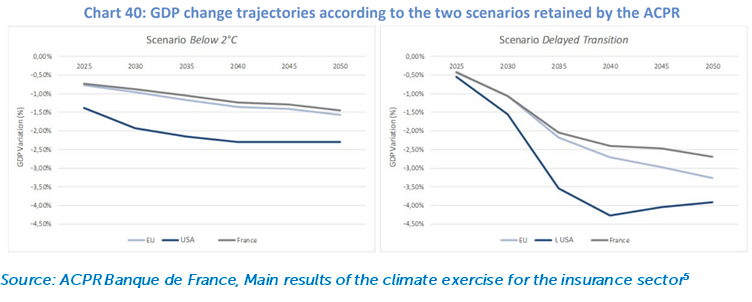

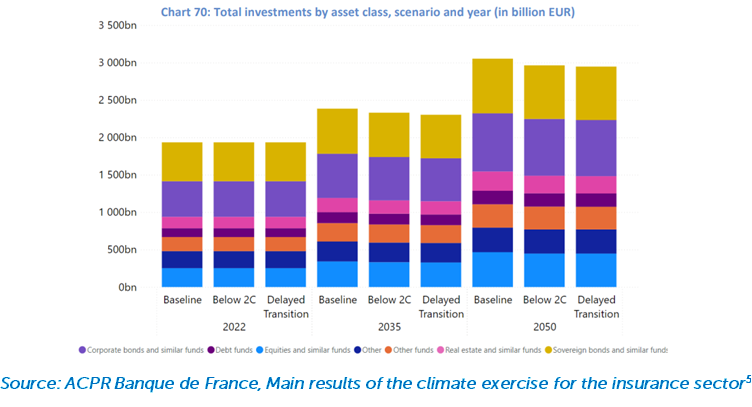

We can see a similar message in the results from the 2023 insurance stress tests by France’s Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution (ACPR), published in May 2024[3]. ACPR developed two long-term stress scenarios based on the Below 2⁰C and Delayed Transition scenarios from the NGFS Phase III update. The projected macroeconomic and financial assumptions are based on the NGFS output. One of the IPCC pathways, RCP 4.5 from AR5[4], was used to derive acute physical risk impacts.

The assumptions run up to the year 2050 and the GDP impacts are up to -3.3% in Europe by 2050. Assumptions for associated investment stresses and insurance hazards are provided by ACPR for various sectors and regions.

The cumulative balance sheet result across all participants was a 3.0% and 3.5% decrease in total assets in 2050 in the Below 2⁰C and the Delayed Transition scenarios, respectively, versus the baseline 2050 projected result.

The projected value of claims by 2050 is higher under the adverse acute physical risk assumptions, particularly for NatCat claims which are 42% or €1.35bn higher relative to the baseline 2050 projected result. Claims on other lines of business including life and health are projected to increase also, albeit to a lesser extent. However, projected loss ratios are maintained at a relatively stable level across the projection because insurance premiums can be increased in response to increasing claims. The ACPR also performed some analysis on the decrease in demand for insurance as the insurance premiums increase which is another area of uncertainty, and governments are eager to understand the climate protection gap.

Many insurers experienced similarly mild impacts when running their internal scenarios derived from the NGFS and IPCC data. Many determined that such low-level impacts do not indicate a need to alter investment strategies or justify investment of resource to investigate further. Investing scarce resources to run such complex and long-term projections only to see such mild results left many insurers feeling that this was a fruitless labour.

Perhaps projecting the balance sheet and business plan over several decades is not the most practical nor efficient approach for insurers to follow when investigating their resilience and vulnerabilities. I believe that companies learn as much about the threats by testing stresses over the ORSA projection period of three to five years. The ACPR saw the value in including a more severe short-term stress scenario in their 2023 exercise also. It is a 5-year scenario involving impacts from extreme weather in France followed by a transition-related market shock, as consumers’ awareness of the threat becomes heightened. The NGFS announced in 2023 that they plan to develop five short-term stress scenarios in future.

These short-term assumption sets will likely become the favoured basis for insurers’ ORSA scenarios in future. They fit better with the ORSA timeline and give insurers an assumption set with some scientific backing, rather than insurers having to derive their own.

Climate models – do end users understand the assumptions?

Another point to consider is whether the mild impacts resulting from the long-term scenarios are due to the fact that the severity of the climate impacts is underestimated in the underlying climate model output. Also, whether the models used to translate the climate changes to impacts on economic variables are realistic. Are we at risk of end users of climate projections placing too much reliance on a low-impact result, without understanding the underlying uncertainty?

These sentiments are echoed in two recent papers from the UK’s Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA), The Emperor’s New Climate Scenarios[6] and Climate Scorpion – the sting is in the tail[7]. Both papers were written in collaboration with the University of Exeter and are well worth reading. They bring several important points to the fore including the fact that the earth systems models, climate impact models, and economic models used to create scenarios like those from NGFS are built on assumptions about many important factors. It is unlikely that these assumptions are all correct, in fact, we appear to be seeing extreme weather at much lower temperature deviation than projected. These IFoA papers point out that negative climate tipping-points are not likely to be adequately allowed for in the scenarios, since damage functions are based on historical data, which makes the results artificially low.

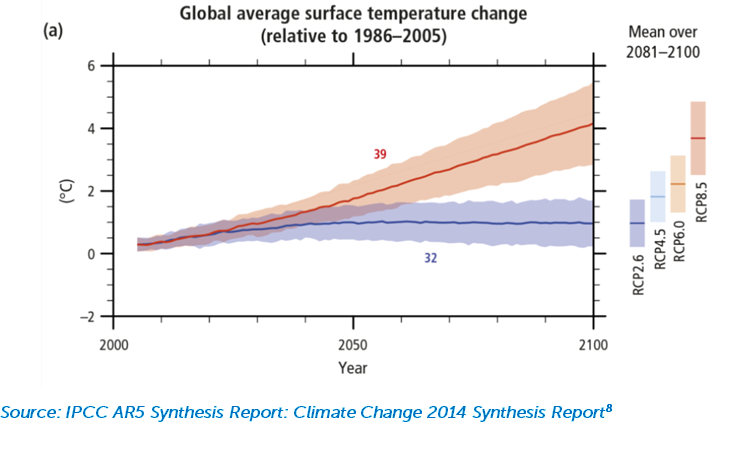

These IFoA papers also remind us that one of the core purposes of enterprise risk management is to assess the extreme, tail events that could result in large losses and test the robustness of the organisation. Publicly available scenarios tend to be built around the average result across the range of underlying models. For example, we see in the below illustration the range of projected results (orange and light blue areas) around the average result (solid orange and blue lines) for two of the pathways in the IPCC AR5 report. The ACPR scenarios use the solid line pathway, the average result.

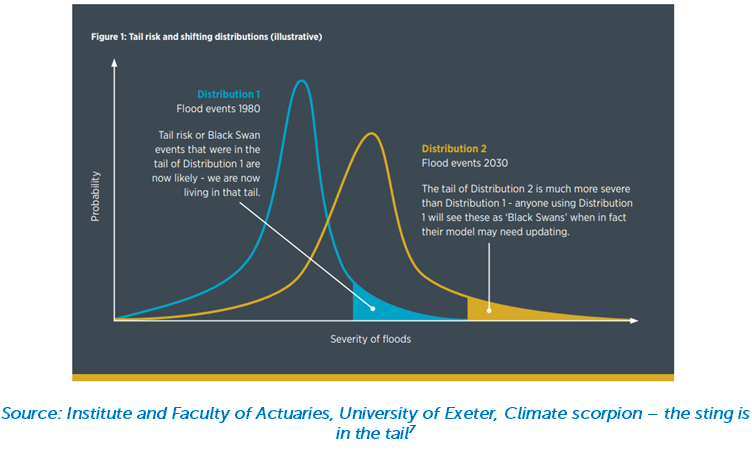

For an ORSA scenario, insurers should not be only assessing results from the average or best-estimate projection. The Climate Scorpion paper highlights the point that climate change has shifted the distribution of weather events, meaning that what was once a tail risk is currently close to an average expectation. For example, what was once a 1-in-100 year flood event could now be a 1-in-5 year event.

This is the type of forward-looking consideration that insurers are asked to incorporate into their scenarios by regulatory bodies. The climate change scenarios need to consider what stressed future state of frequency and severity of events, and stressed transition measures could materialise. Those communicating results of calculated scenarios also have the responsibility to make sure the users of the information understand the high level of uncertainty in the results. It should be made clear that it is highly unlikely that the assumptions and data underlying the financial results have taken adequate account of the range of potential risks.

Setting the baseline outlook for long-term strategy and planning

In our experience, one key exercise at the outset of an ORSA cycle should be establishing a baseline climate change scenario. Insurers should already be allowing for the effects of climate change in their business plan because the industry is already experiencing impacts. For a baseline scenario, using the assumptions in the long-term publicly available “average” scenarios could be considered reasonable – it is a baseline rather than a stress.

The process should involve getting various senior stakeholders in a room to discuss, debate, and approve a baseline for the ORSA projection period and for longer term strategic planning. This fosters ownership of the assumptions and the corporate strategy for facing climate change. It also helps prevent group-think and disagreement later in the process, after stressed scenario assumptions are set or after the modelling teams have calculated the impacts. These conversations and debates should be had early, and at senior levels, including at Board meetings. Under Solvency II, the Board has ultimate responsibility for the management of risks and for compliance with regulation – they must be comfortable with the chosen approach.

A proportionate and risk-based approach

Another point that stands out from our experience is that the approach taken varies significantly depending on the organisation. This is mainly driven by proportionality considerations regarding the materiality of climate change risk for their portfolio and the nature, scale, and complexity of their risk profile. Clearly, a reinsurer with significant natural catastrophe risk in a multitude of global regions will have a sophisticated climate change risk management process. A unit-linked life insurer in northern Europe could justify taking a more simplified and qualitative approach.

The risk management approach should be proportional and pragmatic. The reality is that insurers have to spread their limited resource across many competing tasks. The purpose of climate change risk regulation is not to burden insurers unnecessarily with disproportionate costs. This is made clear in EIOPA’s Opinion1 paper from 2021, where it states “the speed of evolution as well as the scope and granularity of quantification is proportionate to the size, nature and complexity of undertakings’ climate change risk exposures”.

Insurers may decide to perform a point-in-time stress to their year-end balance sheet, in order to assess the stressed solvency ratio. Others will opt to run a one-year stress, perhaps using proxy-models or simplified approaches to scale forward the results over the ORSA projection period. Others may have large modelling teams, sophisticated NatCat models and ALM models, and perform many scenarios to test their business plan and balance sheet. There is value in all types of approach if the results help the insurer understand the potential risk and the need for management actions to be defined and documented.

Remembering the shared mission

When we get caught up in debating the future climate and trying to calculate impacts, it is important to take a step back and remember the core purpose. Many regulatory bodies state a twofold mission with regards to climate risk. One key objective is to increase awareness of the threats and vulnerabilities within the insurer, across all lines of defense, with the aim of improving the stability of the financial system in an uncertain future. The other is to pave the way for funding the low-carbon transition and links to the concept of double materiality.

Transition and adaptation to ensure financial market stability are large-scale challenges and are beyond the scope of any single insurer. They are more so challenges for governments and central banks to grapple with. That said, insurers must be in a position to provide the protection they have promised to their policyholders. Insurers must contribute to the climate-resilience mission by building an understanding of the risks they face and investing sustainably.

Finalyse has gained significant experience in the establishment of climate risk management frameworks and ORSA integration. This stretches from qualitative to quantitative assessments, modelling climate risks by leveraging IPCC scenarios and the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP) projected datasets, which are based on IPCC scenario pathways. We are poised to help you with your climate change analysis. Please reach out to us if you would like to discuss any of the points raised here or any other questions you have on climate change risk.

How can Finalyse help you?

Our team of talented insurance professionals can support you in various areas:

- Risk Management integration for climate change risks, including performing a gap analysis, developing a roadmap for integration, and updating relevant policies and procedures.

- Climate risk identification and materiality assessment on your asset and liability portfolios, defining data requirements, performing the materiality assessment, and hosting workshops to facilitate the process.

- Climate change scenario definition in line with regulatory requirements, including setting the high-level narratives and climate pathways, and defining more granular demographic and macroeconomic assumptions.

- Modelling and impact quantification to translate climate projections into financial and underwriting impacts, including the mapping of climate risks to traditional prudential risks, and deciding on the modelling approach for the short and long term.

- Regulatory Stress Tests: Support with performing the stress tests and balance sheet projections, quantifying climate-related financial impacts, and preparing all the necessary documentation and templates for submission.

- Strategy and business planning to incorporate climate change considerations, including possible management actions, business model changes, and identifying future opportunities and product innovation.

- Benchmarking on topics such as the use of qualitative vs. quantitative assessments, simplified projection options and publicly available tools, and providing insight from our dealings with EIOPA and local regulators.

[1]www.eiopa.europa.eu/eiopa-issues-opinion-supervision-use-climate-change-risk-scenarios-orsa-2021-04-19_en

[2]https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/publications/application-guidance-climate-change-materiality-assessments-and-climate-change-scenarios-orsa_en

[3]acpr.banque-france.fr/en/main-results-climate-exercise-insurance-sector

[4]https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar5/

[5]acpr.banque-france.fr/sites/default/files/medias/documents/20240527_main_results_of_the_cli mate_exercise_insurance_sector_2024_en.pdf

[6]actuaries.org.uk/emperors-new-climate-scenarios

[7]https://actuaries.org.uk/media/g1qevrfa/climate-scorpion.pdf

Finalyse InsuranceFinalyse offers specialized consulting for insurance and pension sectors, focusing on risk management, actuarial modeling, and regulatory compliance. Their services include Solvency II support, IFRS 17 implementation, and climate risk assessments, ensuring robust frameworks and regulatory alignment for institutions. |

Our Insurance Services

Check out Finalyse Insurance services list that could help your business.

Our Insurance Leaders

Get to know the people behind our services, feel free to ask them any questions.

Client Cases

Read Finalyse client cases regarding our insurance service offer.

Insurance blog articles

Read Finalyse blog articles regarding our insurance service offer.

Trending Services

BMA Regulations

Designed to meet regulatory and strategic requirements of the Actuarial and Risk department

Solvency II

Designed to meet regulatory and strategic requirements of the Actuarial and Risk department.

Outsourced Function Services

Designed to provide cost-efficient and independent assurance to insurance and reinsurance undertakings

Finalyse BankingFinalyse leverages 35+ years of banking expertise to guide you through regulatory challenges with tailored risk solutions. |

Trending Services

AI Fairness Assessment

Designed to help your Risk Management (Validation/AI Team) department in complying with EU AI Act regulatory requirements

CRR3 Validation Toolkit

A tool for banks to validate the implementation of RWA calculations and be better prepared for CRR3 in 2025

FRTB

In 2025, FRTB will become the European norm for Pillar I market risk. Enhanced reporting requirements will also kick in at the start of the year. Are you on track?

Finalyse ValuationValuing complex products is both costly and demanding, requiring quality data, advanced models, and expert support. Finalyse Valuation Services are tailored to client needs, ensuring transparency and ongoing collaboration. Our experts analyse and reconcile counterparty prices to explain and document any differences. |

Trending Services

Independent valuation of OTC and structured products

Helping clients to reconcile price disputes

Value at Risk (VaR) Calculation Service

Save time reviewing the reports instead of producing them yourself

EMIR and SFTR Reporting Services

Helping institutions to cope with reporting-related requirements

CONSENSUS DATA

Be confident about your derivative values with holistic market data at hand

Finalyse PublicationsDiscover Finalyse writings, written for you by our experienced consultants, read whitepapers, our RegBrief and blog articles to stay ahead of the trends in the Banking, Insurance and Managed Services world |

Blog

Finalyse’s take on risk-mitigation techniques and the regulatory requirements that they address

Regulatory Brief

A regularly updated catalogue of key financial policy changes, focusing on risk management, reporting, governance, accounting, and trading

Materials

Read Finalyse whitepapers and research materials on trending subjects

Latest Blog Articles

Contents of a Recovery Plan: What European Insurers Can Learn From the Irish Experience (Part 2 of 2)

Contents of a Recovery Plan: What European Insurers Can Learn From the Irish Experience (Part 1 of 2)

Rethinking 'Risk-Free': Managing the Hidden Risks in Long- and Short-Term Insurance Liabilities

About FinalyseOur aim is to support our clients incorporating changes and innovations in valuation, risk and compliance. We share the ambition to contribute to a sustainable and resilient financial system. Facing these extraordinary challenges is what drives us every day. |

Finalyse CareersUnlock your potential with Finalyse: as risk management pioneers with over 35 years of experience, we provide advisory services and empower clients in making informed decisions. Our mission is to support them in adapting to changes and innovations, contributing to a sustainable and resilient financial system. |

Our Team

Get to know our diverse and multicultural teams, committed to bring new ideas

Why Finalyse

We combine growing fintech expertise, ownership, and a passion for tailored solutions to make a real impact

Career Path

Discover our three business lines and the expert teams delivering smart, reliable support