Written by Christophe Caers, Senior Consultant

Introduction

In November 2020, the European Central Bank (ECB) released its Guide on Climate-related and Environmental risks (C&E Risk) furthering its goal to improve the resilience of the European banking system. The publication included 13 recommendations related to integrating C&E risks in banks’ Business Strategy, Governance and Risk appetite and Risk Management Frameworks. Following the release, the ECB instructed the banks to report on the progress of complying with the 13 expectations based on a self-assessment. Later in 2022, the ECB launched the thematic review, which involved conducting deep dives into the institutions’ climate-related and environmental strategies.

The results of the thematic review were summarized in the Walking the Talk paper, which was released on the 2nd November 2022, together with the future deadlines by which the banks should comply with the expectations formulated in the ECB Guide. In the same press release, the ECB provided the banks with a set of best practices that were discovered during the thematic review. The report aims to share observations and good practices illustrating how institutions can align their practices with the expectations.

Materiality Assessment

Article 73 of CRD states that institutions should have processes in place to assess and maintain the internal capital that is considered adequate to cover the risks to which they are exposed. The assessment of the materiality of risk plays a crucial role in the internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP), risk management and overall strategy.

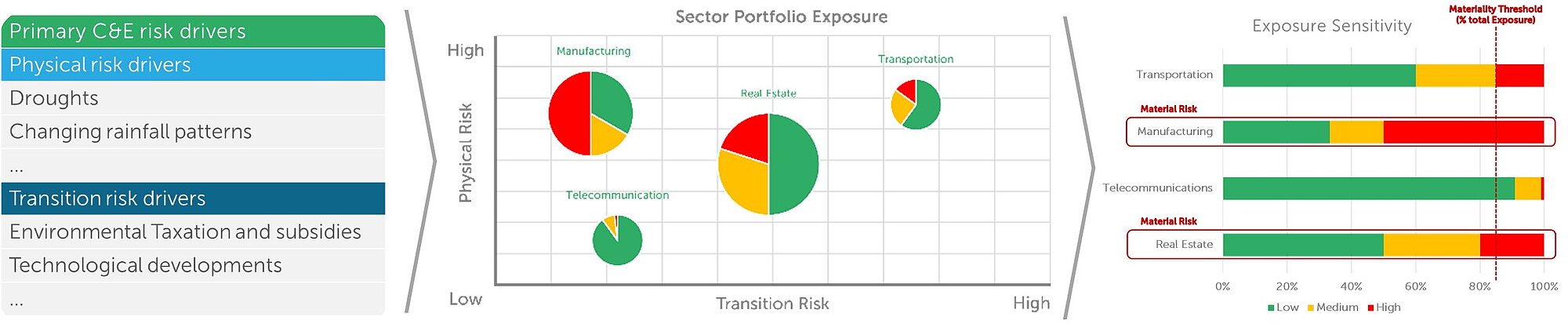

With respect to C&E risks, banks recognise that these function as risk drivers that materialise in existing prudential risk categories. As part of the identification process, institutions rely on bottom-up identification approach where an exhaustive list of C&E risk drivers is composed based on both internal and external expertise. The derived inventory is analysed in order to assess which of the collected C&E risks could have an influence on the risk profile or operations. This can be executed in the form of a heatmap where for each of the sectors, subsectors and geographies in which the bank is active, a judgement is made on the severity of the identified physical and climate risk drivers. The reasoning can be supported by available information, such as emission data and third-party ratings. However, when using the latter, banks should remain wary of the rating methodology used by the provider which often remains (partly) undisclosed, making it challenging to ensure that the weighting and purpose of the score is aligned with the strategy of the bank.

To assess the materiality of the risks, banks should reflect the sensitivity of their own exposures. Depending on the exposure type, different qualitative and quantitative measures will need to be used. The used methodologies can range from relatively low complexity where physical risk is assessed by the creation of sector-geography metrics which scores the sensitivity from high to low to which the exposures are mapped. More complex methodologies are used by leading institutions which rely on counterparty specific information such as a building’s energy consumption, building materials, etc. which are then used to estimate the probability of the collateral becoming non-compliant with EU regulations (and turning into a stranded asset) to assess the exposure to transition risk. The result from the assessment will be used as input for the materiality assessment. Institutions are opting for different methods of threshold determination. This could be based on the capital and/or liquidity impact, a qualitative assessment reflecting the expected impact on the institutions’ reputation and liability or a concentration threshold where the size of the exposure-at-risk is compared relative to the total exposure. After the determination of materiality is completed, institutions take action to ensure their risk management framework and processes address the material risk.

Business Strategy

The ECB found that in terms of business strategy, banks are opting for a strategic approach to manage climate risks where transition planning and target setting have started playing a central role. In the context of transition risks, banks would use the results from the materiality assessment as a starting point, where they would zoom-in on for example, the most sensitive industries. The related target setting would then be translated in the form of Key Risk Indicators (KRIs), this could be a set of targets by sectors combined with a reduction in financed emissions set over several horizons for each of them. The targets are based on forward-looking and science-based decarbonization pathways. Furthermore, institutions rely on Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) methodologies for measuring financed emissions and Paris Agreement Capital Transition Assessment (PACTA) for forward-looking (4-5 years ahead) measurement of alignment portfolios using scenario-based transition pathways. Whilst there is a degree of variation in the intermediate targets set between different sectors, there is also notable variation within those sectors which is more surprising this is the result of dispersion in the used scenarios and the heterogeneity in starting points for sector portfolios in different banks. The institution would integrate the targets and attention thresholds into the existing monitoring and escalation procedures when they would be breached.

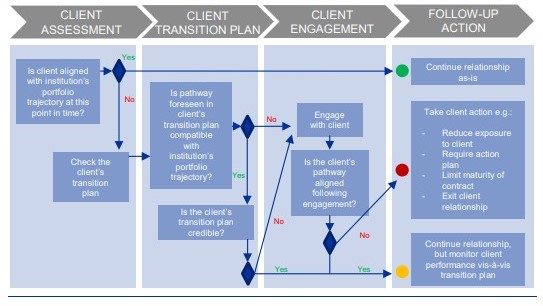

The ECB paper indicates that client engagement is used as a powerful steering tool to align banks’ portfolios with their strategic goals. In this approach the current situation of a counterparty would be reviewed against the intended trajectory of the institution as indicated in Figure 2 of the paper. If not aligned, the bank would review the transition plan of the client and verify if it is in line with the desired portfolio pathway. Moreover, the banks would assess the credibility of the transition plan. If not, the banks would enter a dialogue with the client to re-adjust and define actions. If the engagement is unsuccessful, actions could be taken to reduce the exposure or to refuse the renewable contracts.

Governance and Risk Appetite

Institutions are increasingly addressing C&E risks considerations in the setup of the management structure. In many institutions, the management body approves the environmental strategy and risk management framework and the corresponding policies and implementation. Banks will create dedicated committees consisting of subject matter experts that deliver advice to the management body on environmental matters such as changes to the environmental strategy and policies, net-zero commitments, Risk Appetite Framework (RAF) and the adequacy of the management process. Several institutions were found to have opted for the combination of a top-down and bottom-up approach. In this setup, the bank's decision-making body discusses the strategies related to, for instance, net-zero commitments and related decisions. Representatives of the relevant business lines are included as to contribute to these discussions from the ground up and to gather verification of the integration of the environmental strategy into the daily operations.

To align the incentives of the members of the management body and senior management with the C&E related strategy goals of the bank, the remuneration policy is adjusted accordingly. Parts of the variable remuneration components are based on KPIs that track whether the predefined targets have been reached, such as a reduction in financed emissions, an increase in the sale of green finance products or whether the institution attains a predetermined level of sustainability rating from a rating agency.

On the side of the Risk Appetite Framework (RAF), institutions have started including granular and forward-looking information. These KRIs could represent the alignment of the banks' portfolio with the chosen transition trajectory. Beyond the quantitative KRIs, institutions have established indicators that monitor the roll-out of or the adherence to the climate-related risk management policies, such as credit risk assessment processes. As such, the KRIs do not measure an institution's exposure to risk but rather its level of success in terms of rolling out climate-related risk management policies throughout the organisation. The compliance with the selected KRIs is monitored in the same fashion as other indicators using the red, amber, green approach. For the red and amber levels, the institutions will define roles, responsibilities and deliveries that should be drafted such as a remediation plan.

KRI | Description |

Portfolio alignment | The KRI shows the distance between the desired portfolio trajectory of a specific sector and the banks’ actual situation. If the portfolio exposure is above the trajectory at a given point in time by a defined percentage, procedures are triggered in line with predefined governance processes. |

Financed Emissions | The KRI shows the financed emissions in the lending and investment portfolio. |

Limit on the sectoral level | Institutions might define quantitative limits on the sector level both in absolute and relative terms for those industries with elevated sensitivity to transition and physical risks. |

Figure 3 : KRI examples overview

Institutions are creating reporting frameworks for C&E risks including putting in place governance structures to support the related data strategy. The architecture is usually centralised within a steering committee to oversee the project. The committee might be chaired by a member of the management and includes members of several business areas to get a broad coverage of risk functions and local subsidiaries. The exercise starts with a data gap analysis. First, an aggregation is made of all current and oncoming data requirements such as risk management needs, business objectives and commitments related to target setting. Once an exhaustive list of data needs is formulated, the institutions will carry out a data gap analysis which in addition to the aforementioned data collection needs will include an assessment of the requirement IT infrastructure and risk data aggregation capabilities. To enhance the completeness of their C&E risk data, banks will complement internal information with external sources while establishing a hierarchy of data sourcing. In the latter actual client data will hold priority while being supplemented by external data, if both are not available, proxy approaches will be employed. Institutions are increasingly recognising the importance of using dedicated C&E risk questionnaires to collect client or asset level data. These questionnaires are being embedded in the due diligence process and client engagement procedures. On the side of third party data providers, institutions should carry out an assessment of its data providers covering aspects such as completeness and data quality. Furthermore, a set of criteria could be defined that is used to prioritize or facilitate the selection of a third party data provider.

The above outlined framework from the good practices papers provides a solid foundation for financial institutions to start building their internal C&E data architecture. However, it might be challenging for banks to currently create an exhaustive outline of all data requirements. The fast-paced development of the C&E-risk and ESG-practices requires constant monitoring of regulatory and market demands to ensure being up-to-speed with the relevant data needs. The framework will need frequent adjustments to ensure internal and external compliance. Moreover, while sustainability related disclosures are maturing, it is likely that for retail counterparts banks will have to rely on self-disclosure of their counterparties in the form of questionnaires. The ability of the banks to receive accurate data from counterparties on a recurrent basis is pertinent given their needs to monitor the evolution and alignment of counterparties in line with submitted transition plans. Financial institutions should ensure that the reporting process is streamlined and does not put excessive reporting-stress on their client base and provide transparent incentives to release the requested data. Moreover, resources will need to be invested to train counterparties who are not participating in other reporting requirements such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) (the latter will be replaced by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)). While some requested data points, such as for instance water usage, might be easier to report, others require technical knowledge and training such as the calculation of Scope 1, 2 and 3 Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The inability of banks to educate their clients will result in them foregoing reporting or resorting to proxy approaches based on for example sector averages. The latter might result in a diminished ability of the bank to distinguish between counterparties in terms of greenhouse gas intensity, therefore affecting the discriminatory power of the information. Regulatory initiatives centralizing such information in a single data base such as the European Single Access Point (ESAP) will improve data availability to the banking system. Moreover, it will alleviate the regulatory burden on counterparties when interacting with multiple financial institutions as in the future such information will be shared.

Risk Management

As part of the due diligence process, institutions have started to screen clients in relation to the exclusion criteria set in lending policies. The lending criteria define which sectors and/or activities are in line with the banks’ risk appetite. For counterparties that are not excluded based on the criteria, the institutions will continue the due diligence process based on client-level assessment. This will to a large extent rely on a questionnaire sent to the client and asset level data such as GHG emissions, fossil fuel dependency, adverse media attention, etc. Based on the collected data, banks will be able to instigate a level of C&E risk differentiation and rank counterparties with their peers. Based on the result, a decision will be taken if the risk is acceptable and within their risk appetite. Institutions will need to have in place an overall threshold of high-risk clients they wish to accept either as proportion of the portfolio or defined as an absolute threshold.

The information collected in the questionnaire can, as previously mentioned, be used in a stand-alone scorecard which will be factored in during lending decisions. Additionally, it could be integrated into credit risk rating systems such as the Probability of Default (PD). As part of the rating process, institutions could take into consideration C&E data and/or environmental risk ratings from external providers in the form of a qualitative score or as an override reason. Based on the result of the assessment, a downgrade of the PD rating could be warranted.

In terms of operational risk, institutions have been seen to assess the impact of physical risk on their own operations using forward-looking scenario analysis. For each region in which the institution is active, the most material physical risk events are identified based on collected information from external data providers. The institution then assesses which of its office buildings, recovery sites and third-party providers may be exposed to the risk events. Based on the resulting vulnerability remediating actions might be taken, such as relocation or creating safety/resolution procedures.

Institutions are starting to integrate C&E risks in collateral valuations and pricing. However, this is still in the early stages of development. The integration is done in two ways. First, it is integrated into the cost price calculations of their loan prices. This is done by integrating risk factors in the calculation of credit and funding costs. Second, financial institutions reflect C&E-related factors in certain lending products' expected profit margin requirements. One way to integrate is to offer sustainability-linked loans. In this setup, the conditions of the loan terms are conditional on achieving certain KPIs. The targets are set at certain intervals with increasing thresholds and monitored accordingly. Depending on whether the targets are met, the debtor receives an interest rate discount or penalty.

Some banks have started to consider physical and transition risk drivers in the valuation and management of collateral. Specialized software can be used to assess the physical risk of assets based on the probability of occurrence of a natural hazard and the vulnerability of that asset. The assessment is conducted on a location-specific basis to quantify physical risk using geospatial mapping and geographical characteristics. The final results are translated into expected damages and losses that are taken into account for the valuation of collateral. Other institutions include transition risk by considering the energy label of the property in the valuation report, which may affect the LGD and, thus expected credit losses.

Several institutions have started assessing the capital adequacy related to C&E risks as part of their ICAAP. Such assessments are conducted using scenario analysis in order to take into account forward-looking factors over a longer time horizon. In the case of credit risk, institutions are leveraging scientific climate pathways (as for example, provided by Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)) to assess physical and transition risks. The used scenarios simulate the stressed impact on the portfolio. One of the used models can estimate the changes in earnings of a counterparty and the effect on the PD over various time horizons. The counterparty results can be aggregated to get an estimate of the portfolio impact. On the side of operational risk, institutions consider several climate-related risk drivers that could trigger an operational risk impact. The used scenarios could consider the damage to physical assets due to a flood event, disruption of business or system failures, non-compliance with sustainability-related regulation, etc. For each of the scenarios, the institutions develop loss estimates taking into account a range of hypothetical impacts such as remediation costs, legal costs, client compensation and asset write down or foregone revenue. The estimates can be based on historical loss events.

Conclusion

The results of the thematic review demonstrate that the European banking sector still has strides to take to fully integrate C&E risk considerations across their business and risk management practices. Due to the novelty of the topic, many financial institutions have struggled to make significant process in the past years as very limited information is available or no market practices have been established. With the release of ‘Good practices for climate-related and environmental risk management’, the ECB recognized that industry-wide knowledge sharing will be pertinent for promoting and acceleration in the practices adoption. The provided examples and best practices in the report bring valuable starting point to financial institutions aiming to improve their internal operations and frameworks.

Finalyse InsuranceFinalyse offers specialized consulting for insurance and pension sectors, focusing on risk management, actuarial modeling, and regulatory compliance. Their services include Solvency II support, IFRS 17 implementation, and climate risk assessments, ensuring robust frameworks and regulatory alignment for institutions. |

Our Insurance Services

Check out Finalyse Insurance services list that could help your business.

Our Insurance Leaders

Get to know the people behind our services, feel free to ask them any questions.

Client Cases

Read Finalyse client cases regarding our insurance service offer.

Insurance blog articles

Read Finalyse blog articles regarding our insurance service offer.

Trending Services

BMA Regulations

Designed to meet regulatory and strategic requirements of the Actuarial and Risk department

Solvency II

Designed to meet regulatory and strategic requirements of the Actuarial and Risk department.

Outsourced Function Services

Designed to provide cost-efficient and independent assurance to insurance and reinsurance undertakings

Finalyse BankingFinalyse leverages 35+ years of banking expertise to guide you through regulatory challenges with tailored risk solutions. |

Trending Services

AI Fairness Assessment

Designed to help your Risk Management (Validation/AI Team) department in complying with EU AI Act regulatory requirements

CRR3 Validation Toolkit

A tool for banks to validate the implementation of RWA calculations and be better prepared for CRR3 in 2025

FRTB

In 2025, FRTB will become the European norm for Pillar I market risk. Enhanced reporting requirements will also kick in at the start of the year. Are you on track?

Finalyse ValuationValuing complex products is both costly and demanding, requiring quality data, advanced models, and expert support. Finalyse Valuation Services are tailored to client needs, ensuring transparency and ongoing collaboration. Our experts analyse and reconcile counterparty prices to explain and document any differences. |

Trending Services

Independent valuation of OTC and structured products

Helping clients to reconcile price disputes

Value at Risk (VaR) Calculation Service

Save time reviewing the reports instead of producing them yourself

EMIR and SFTR Reporting Services

Helping institutions to cope with reporting-related requirements

CONSENSUS DATA

Be confident about your derivative values with holistic market data at hand

Finalyse PublicationsDiscover Finalyse writings, written for you by our experienced consultants, read whitepapers, our RegBrief and blog articles to stay ahead of the trends in the Banking, Insurance and Managed Services world |

Blog

Finalyse’s take on risk-mitigation techniques and the regulatory requirements that they address

Regulatory Brief

A regularly updated catalogue of key financial policy changes, focusing on risk management, reporting, governance, accounting, and trading

Materials

Read Finalyse whitepapers and research materials on trending subjects

Latest Blog Articles

Contents of a Recovery Plan: What European Insurers Can Learn From the Irish Experience (Part 2 of 2)

Contents of a Recovery Plan: What European Insurers Can Learn From the Irish Experience (Part 1 of 2)

Rethinking 'Risk-Free': Managing the Hidden Risks in Long- and Short-Term Insurance Liabilities

About FinalyseOur aim is to support our clients incorporating changes and innovations in valuation, risk and compliance. We share the ambition to contribute to a sustainable and resilient financial system. Facing these extraordinary challenges is what drives us every day. |

Finalyse CareersUnlock your potential with Finalyse: as risk management pioneers with over 35 years of experience, we provide advisory services and empower clients in making informed decisions. Our mission is to support them in adapting to changes and innovations, contributing to a sustainable and resilient financial system. |

Our Team

Get to know our diverse and multicultural teams, committed to bring new ideas

Why Finalyse

We combine growing fintech expertise, ownership, and a passion for tailored solutions to make a real impact

Career Path

Discover our three business lines and the expert teams delivering smart, reliable support